J. Biosci. Public Health. 2025; 1(3)

This cross-sectional study investigates the association between parental bonding and parent-child relationships among college-going adolescents in Bangladesh. Utilizing a semi-structured questionnaire based on Robert C. Pianta's Nexus Scale, data were collected from 101 college students aged 17-19 of Chattogram in Bangladesh. The findings reveal a distinct disparity in the quality of relationships with mothers versus fathers. A majority of participants (62.4%) reported feeling delighted spending time with their mother, compared to 49% who were very happy spending time with their fathers. Conversely, a very small proportion expressed dissatisfaction (5.9% unhappy/very unhappy with mothers; 3.5% unhappy with fathers). Analysis of bonding showed that a significant proportion (almost 40%) reported a strong bond with their mothers. In contrast, a strong bond with the father was less common (approximately 30%). Furthermore, over three-quarters of respondents indicated disagreements with their father concerning proximity and dependence. When measuring overall intimacy, a sizable proportion reported low levels: nearly 30% had low intimacy with their mothers, and over 40% had low intimacy with their fathers. Statistical analysis confirmed that overall relationship intimacy with both parents was significantly correlated (p<0.000) with key relationship characteristics, including conflict, closeness, and dependence. Additionally, several aspects of the parent-child relationship were found to have a marginally significant association with gender. These included the things participants liked (p<0.05) and disliked (p<0.04) most about their mothers, their feelings when spending time with their mothers (p<0.05), and the things they disliked most about their fathers (p<0.05).

The bond between a parent and child is fundamental to human development and has a significant impact on a person's social, emotional, and cognitive development. Long-term psychological effects and interpersonal dynamics are impacted by this bond, which is frequently based on childhood memories [1]. Obviously, child improvement inquiries have centered on the parent-child relationship in order to better understand how it develops and its capacities through time. A cherishing, mindful, and accommodating parent who is continually showing up for their child serves to tie the child to them, concurring to investigate, and contributes to the complementary flow of that authority [2]. Parental holding is characterized as the child's connection to his or her guardians. This connection hypothesis is based on the introduction that there are personal contrasts in how newborn children ended up candidly joined to their essential caregivers and how these early connection encounters influence infants' future social, cognitive, and enthusiastic advancement. The parent's state of mind and behavior toward the infant's needs, agreeing with Bowlby, decides the connection [2]. When a caregiver responds to a kid's demand in a sensitive and consistent manner, the youngster develops a secure bond. Insecure attachment is the result of parents who frequently ignore or reject their children's demands for attention. Adults who are firmly attached are more competent, gregarious, and comfort table in dealing with many types of relationships in life, according to studies [3]. When compared to their insecurely attached colleagues, they are more likely to maintain a higher level of self-reliance and self-esteem [1]. Insecurely linked adults, on the other hand, were more likely to participate in antisocial activities, suffer from melancholy and anxiety, and be clingy, dependent, and lacking in self-confidence [4]. Parker et al. developed the Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI) to examine parental traits-caring and overprotection-that may contribute to the quality of attachment between parent and child [5]. Twelve of the PBI's elements are categorized as care items (e.g., affection, emotional warmth, empathy, and intimacy vs. emotional coldness, apathy, and neglect), while the remaining 13 are classified as protection or control items (e.g., overprotection, intrusion, control, and prevention of independence versus interdependence and autonomy) [5].

In expansion, "parent-child association" (PCC) may be a word utilized to characterize a persevering bond between a parent and a child [6]. The PCC is calculated based on two components: control and warmth. Warmth figure characteristics incorporate belief, adaptability, shared positive thinking, independence, or warmth [7], though control calculates guardians are more likely to deny their children decision-making or constrain their opportunity in making companions [8]. PCC inquiry has looked at the continuous relationship between guardians and children, which is ordinarily characterized in terms of distinctive parenting styles, counting as definitive, dictatorial, lenient, and careless parenting. Definitive child rearing is characterized by a combination of solid warmth and direct control [8]. Authoritarian parenting, on the other hand, is characterized by a high level of control through thorough rules, and lenient or permissive parenting is defined by a low or high amount of warmth combined with a low level of control. The foremost advantageous child-rearing fashion is definitive parenting (high warmth-moderate control), in which guardians are regularly sincerely warm, tender, and able to combine a set of firms, however reasonable, disciplinary styles [8]. They are able to create an enthusiastic environment in which the parent-child network (PCC) is tall as a result of this. A few analysts have utilized specific concurrent combinations of the parent's and child's behavior to capture dyadic characteristics such as associations and synchrony in order to capture the dyadic highlights of the relationship [9]. Kochanska proposed a construct called mutually responsive orientation (MRO) with two primary components: reciprocal responsiveness and shared happy times between parent and child [10].

At the infant, little child, and preschool levels, these components are coded amid naturalistic intelligence between guardians and children. MRO investigation has presently developed and gone past the two components. The Commonly Responsive Introduction Scales (MROS) were made by Aksan et al. to portray four key components: planning strategies, consonant communication, shared participation, and passionate climate. Guardians and children who have a tall MRO-level construct facilitate consistent and easy-to-follow schedules, permitting them to peruse each other's signals and communicate viably [11]. They too have a solid inclination to work together and react to one another. Moreover, they are more likely to have visit bouts of charm, shows of common warmth, and humor, as well as proficiently minimize negative influence once it occurs.

In Bangladesh, studies exploring parent-adolescent relationships have primarily focused on specific contexts, such as reproductive health communication between mothers and daughters [12] or general adolescent-parent dynamics [13]. However, there is a noticeable gap in research examining the quality of parent-child relationships among college-going adulthood in Bangladesh. This demographic, navigating the transition from adolescence to adulthood, faces unique challenges that may influence their familial bonds. This study addresses this gap by investigating the nexus quality between college-going adolescents (aged 17-19) and their parents in Chattogram, using a cross-sectional approach based on the Nexus Scale by Robert C. Pianta. By exploring dimensions such as closeness, conflict, and dependence, this research aims to provide insights into the dynamics of parental bonding and its implications for adulthood well-being from a public health perspective.

2.1. Study Design

This cross-sectional study employed a descriptive design to investigate the quality of parent-child relationships among college-going adolescents in Chattogram, a major educational and commercial hub of Bangladesh. Data collection occurred between August 2022 and March 2023 at two purposively selected colleges in Chattogram.

2.2. Sampling Technique

A purposive sampling technique was used to select the study population. Participants were students aged 17-19 years enrolled in Standard XII (higher secondary level) at Chattogram Biggan College and Chattogram Commerce College. Both male and female students were eligible for inclusion. A total of 101 students were recruited based on their availability and willingness to participate. The selection of these colleges was based on convenience, reflecting their prominence in the region and accessibility for data collection.

The sample size was determined using a single proportion formula for a population.

n =

n = preferred sample size.

n = preferred sample size.

Here, Z=the standard normal distribution set as 1.96 (95% confidence interval), P = Proportion in the target population estimated; p=0.5, 1-P = proportion in the target population; 1-0.5=0.5, d = degree of accuracy required (set at 0.05 a marginal error).

Based on this, n =  = 384

= 384

So, the sample size was estimated as 384. However, due to the post-COVID-19 pandemic situation and the financial constraints along with the rigid timing, data were collected from 101 participants.

2.3. Data Collection

A semi-structured questionnaire was prepared, which comprised items focusing on parent-child relationships. Data were collected face-to-face by both interviewing and self-administration depending on the patient’s educational status. Robert C. Pianta (1992) recommended the Child-Parent Relationship Scale [14], which has been used to measure the levels of intimacy among parents. Summation of the items as noted; each question has a score from 0 to 4. While the replies are coded as definitely does not apply=0; not really=1; neutral, not sure=2; applies somewhat=3; and definitely applies=4. To establish the mean, divide the sum by the number of questions in that section. Mean (average) closeness scores for mother and father were 37 and 35.5, respectively. Moreover, for mothers, the mean score of conflicts was 15.5, whereas for fathers, this score was 14.5.

2.4. Data Analysis

The data were analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 23. Data were presented in the form of Tables and graphs, followed by the interpretation of the results. A chi-square test was conducted to explore the association. A p-value level of <0.05 was considered to test statistical significance.

The socio-demographic profile of the 101 respondents reflects that 46% are male and 54% are female among 101 respondents. 39.6% of the total participants are 17 years old, whereas 56.45% of the total participants are 18-year-old and the remaining 3.96% of participants are 19 years old. Table 1 presents the distribution of conflicts with the mothers of the participants. Most of the participants (57.4%) reported that their mothers ‘always’ worried too much about them. 32.7% of participants reported that their mothers ‘never’ argued with them. 66.3% of the participants answered that their mother ‘never’ failed to care about them; likewise, 53.5% of participants reported that they ‘never’ felt unimportant to their mother. 44.6% and 53.5% reported that their mother ‘never’ beat them and hit them with objects, respectively. A small group (9.9%) reported that their mother told them they are worthless, while most of the participants (48.5%) answered they never felt that way. 47.5% of participants reported that their mothers ‘often’ allowed them to decide for themselves. 39.6% said that their mothers are ‘always’ afraid they could have bad company. 6.9% reported that their mothers ‘always’ shouted at them, and 20.8% reported that their mothers ‘always’ nagged them.

Table 1. Frequency distribution of the relationship matrix (conflicts, closeness and dependence) with the mother of the respondent (n=101).

| Variables | Never (%) | Rarely (%) | Sometimes (%) | Often (%) | Always (%) |

| Parameter: Conflict | |||||

| My mother has worried too much about me | 3 | 8.9 | 19.8 | 10.9 | 57.4 |

| My mother as argued with me | 32.7 | 22.8 | 27.7 | 8.9 | 7.9 |

| My mother didn't care about me | 66.3 | 1 | 5 | 11.9 | 15.8 |

| My mother has beaten me | 44.6 | 7.9 | 17.8 | 15.8 | 13.9 |

| My mother has told me that I’m worthless | 48.5 | 11.9 | 12.9 | 16.8 | 9.9 |

| My mother and I have disagreed | 46.5 | 15.8 | 11.9 | 12.9 | 12.9 |

| I have been of no importance to my mother’s | 53.5 | 3 | 15.8 | 10.9 | 16.8 |

| My mother has punished me too hard | 56.4 | 12.9 | 10.9 | 6.9 | 12.9 |

| My mother has allowed me to decide for myself | 5.9 | 5.9 | 16.8 | 47.5 | 23.8 |

| I had to do some for my mother than other kids had to do for their mothers | 39.6 | 15.8 | 15.8 | 14.9 | 13.9 |

| My mother has been very angry about me | 47.5 | 12.9 | 10.9 | 12.9 | 15.8 |

| My mother has rejected me | 54.5 | 8.9 | 10.9 | 15.8 | 9.9 |

| My mother has shouted at me | 31.7 | 18.8 | 27.7 | 14.9 | 6.9 |

| My mother has hit me with objects (e.g. shoes, belt) | 53.5 | 8.9 | 26.7 | 5.9 | 5.0 |

| My mother has been afraid I could be around bad company | 21.8 | 15.8 | 15.8 | 6.9 | 39.6 |

| My mother has nagged me | 14.9 | 13.9 | 27.7 | 22.8 | 20.8 |

| Parameter: Closeness | |||||

| My mother has given me the freedom to make my own choices | 10.9 | 5 | 13.9 | 40.6 | 29.7 |

| My mother's opinion has been important to me | 5 | 2 | 9.9 | 23.8 | 59.4 |

| When I really wanted to do something, my mother let me do it | 7.9 | 16.8 | 17.8 | 22.8 | 34.7 |

| My mother and I have enjoyed cuddling with each other (Play fighting, horse playing) | 27.7 | 8.9 | 14.9 | 21.8 | 26.7 |

| I had to console my mother | 18.8 | 11.9 | 23.8 | 13.9 | 31.7 |

| When I needed my mother, she has been there for me | 5.9 | 6.9 | 13.9 | 12.9 | 60.4 |

| My mother dreaded that sometimes could happen to me | 28.7 | 14.9 | 21.8 | 17.8 | 16.8 |

| My mother has poured out her heart to me | 22.8 | 11.9 | 12.9 | 20.8 | 31.7 |

| I have cuddled up to my mother (leaned on her) | 33.7 | 12.9 | 24.8 | 9.9 | 18.8 |

| I've had the feeling mother really loves me | 1 | 3 | 9.0 | 14.9 | 71.3 |

| My mother has trusted my decisions | 6.9 | 1 | 21.8 | 32.7 | 37.6 |

| My mother has been an example to me | 2 | 3 | 9.9 | 17.8 | 67.3 |

| In some ways I am just like my mother | 1 | 2 | 20.8 | 43.6 | 32.7 |

| I want to become just like my mother | 3 | 4 | 14.9 | 19.8 | 58.4 |

| Parameter: Dependence | |||||

| My mother as needed my help | 3 | 4 | 11.9 | 25.7 | 55.4 |

| I had to be considerate of my mother, because things easily became | 7.9 | 12.9 | 24.8 | 11.9 | 42.6 |

| My mother has loaded her worries on me | 42.6 | 8.9 | 26.7 | 10.9 | 10.9 |

| I have had to relieve my mother of tasks | 5 | 5 | 21.8 | 16.8 | 51.5 |

| My mother has asked me for advice when she had problems | 9.9 | 15.8 | 35.6 | 17.8 | 20.8 |

| My mother has helped me when I had problems with others | 7.9 | 9.9 | 14.9 | 14.9 | 52.5 |

Regarding participants' perceptions of closeness with their mothers. 71.3%, 67.3%, and 58.4% of participants reported that they ‘always’ felt their mothers love them, their mothers have been the example to them, and they want to become like their mothers, respectively. 31.7% said that they ‘always’ had to console their mother, and also the same proportion said that their mother has poured out their heart to them. 26.7% of people reported that they enjoy cuddling with their mother ‘always.’ 33.7% reported that they ‘never’ cuddled up to their mother (Table 1). A majority of participants (55.4%) reported that their mothers ‘always’ needed their help, and 51.5% reported that they ‘always’ had to relieve their mothers of tasks. Likewise, 42.6% reported that they ‘always’ had to be considerate of their mother. Again, most of the participants (52.5%) reported that their mother ‘always’ helped them whenever they had problems with others (Table 1).

Table 2. Frequency distribution of the relationship matrix (conflicts, closeness and dependence) with the father of the respondent (n=101).

| Variables | Never (%) | Rarely (%) | Sometimes (%) | Often (%) | Always (%) |

| Parameter: Conflict | |||||

| My father has worried too much about me | 1 | 7.9 | 26.7 | 16.8 | 47.5 |

| My father as argued with me | 34.7 | 25.7 | 19.8 | 14.9 | 5 |

| My father didn't care about me | 47.5 | 11.9 | 21.8 | 15.8 | 3 |

| My father has beaten me | 31.7 | 9.9 | 29.7 | 13.9 | 14.9 |

| My father has told me that I’m worthless | 25.7 | 11.9 | 23.8 | 22.8 | 15.8 |

| My father and I have disagreed | 18.8 | 22.8 | 17.8 | 20.8 | 19.8 |

| I have been of no importance to my father’s | 47.5 | 3 | 21.8 | 15.8 | 11.9 |

| My father has punished me too hard | 50.5 | 4 | 15.8 | 15.8 | 13.9 |

| I had to do some for my father than other kids had to do for their fathers | 46.5 | 16.8 | 23.8 | 5 | 5.9 |

| My father has been very angry about me | 27.7 | 9.9 | 25.7 | 13.9 | 22.8 |

| My father has rejected me | 46.5 | 8.9 | 10.9 | 18.8 | 14.9 |

| My father has shouted at me | 34.7 | 11.9 | 20.8 | 18.8 | 13.9 |

| My father has hit me with objects (e.g. shoes, belt) | 52.5 | 10.9 | 18.8 | 9.9 | 7.9 |

| My father has been afraid I could be around bad company | 13.9 | 15.8 | 21.8 | 12.9 | 35.6 |

| My father has nagged me | 22.8 | 18.8 | 25.7 | 18.8 | 13.9 |

| Parameter: Closeness | |||||

| My father has given me the freedom to make my own choices | 11.9 | 7.9 | 31.7 | 29.7 | 18.8 |

| My father's opinion has been important to me | 2 | 6.9 | 21.8 | 18.8 | 50.5 |

| When I really wanted to do something, my father let me do it | 6.9 | 7.9 | 39.6 | 23.8 | 21.8 |

| My father and I have enjoyed cuddling with each other (Play fighting, horse playing) | 22.8 | 13.9 | 23.8 | 20.8 | 18.8 |

| I had to console my father | 26.7 | 14.9 | 27.7 | 16.8 | 13.9 |

| When I needed my father, he has been there for me | 5 | 9.9 | 22.8 | 13.9 | 48.5 |

| My father has allowed me to decide for myself | 6.9 | 12.9 | 37.6 | 19.8 | 22.8 |

| My father dreaded that sometimes could happen to me | 28.7 | 5 | 36.6 | 15.8 | 13.9 |

| My father has poured out his heart to me | 17.8 | 19.8 | 20.8 | 22.8 | 18.8 |

| I have cuddled up to my father (leaned on her) | 43.6 | 12.9 | 18.8 | 16.8 | 7.9 |

| I've had the feeling father really loves me | 4 | 5 | 25.7 | 9.9 | 55.4 |

| My father has trusted my decisions | 1 | 8.9 | 24.8 | 40.6 | 24.8 |

| My father has been an example to me | 5.9 | 2.0 | 15.8 | 17.8 | 58.4 |

| In some ways I am just like my father | 1 | 2 | 27.7 | 34.7 | 34.7 |

| I want to become just like my father | 2 | 2 | 24.8 | 18.8 | 52.5 |

| Parameter: Dependence | |||||

| My father as needed my help | 2 | 6.9 | 14.9 | 30.7 | 45.5 |

| I had to be considerate of my father, because things easily became | 12.9 | 7.9 | 28.7 | 14.9 | 35.6 |

| My father has loaded his worries on me | 44.6 | 5 | 22.8 | 18.8 | 8.9 |

| I have had to relieve my father of tasks | 4 | 4 | 19.8 | 20.8 | 51.5 |

| My father has asked me for advice when he had problems | 12.9 | 21.8 | 30.7 | 17.8 | 16.8 |

| My father has helped me when I had problems with others | 7.9 | 10.9 | 24.8 | 14.9 | 41.6 |

Table 2 shows the distribution of conflicts with the father of the participants. Most of the participants (47.5%) reported that their fathers ‘always’ worried too much about them. 34.7% of participants reported that their fathers ‘never’ argued with them. 47.5% of the participants answered that their father ‘never’ failed to care about them; likewise, 47.5% of participants reported that they ‘never’ felt unimportant to their father. 31.7% and 52.5% reported that their father ‘never’ beat them and hit them with objects, respectively.

Regarding perceptions of closeness with their father. 55.4%, 58.4%, and 52.5% of participants reported that they ‘always’ felt their fathers love them, their fathers have been the example to them, and they want to become like their fathers, respectively. Similarly, 18.8%, 48.5%, and 24.8% of participants answered that ‘always’ their fathers gave them the freedom to make their own choices, their fathers were always there for them, and their fathers trusted their decisions, respectively. 18.8% of people reported that they enjoy cuddling with their father ‘always.’ 43.6% reported that they ‘never’ cuddled up to their father (Table 2). A majority of participants (45.5%) reported that their fathers ‘always’ needed their help, and 51.5% reported that they ‘always’ had to relieve their fathers of tasks. Likewise, 35.6% reported that they ‘always’ had to be considerate of their father. 44.6% said that their father ‘never’ loaded her worries on them, though 22.2% experienced it ‘sometimes.’ 30.7% reported that ‘sometimes’ their father has asked them for their advice when they had problems. Again, most of the participants (41.6%) reported that their father ‘always’ helped them whenever they had problems with others (Table 2).

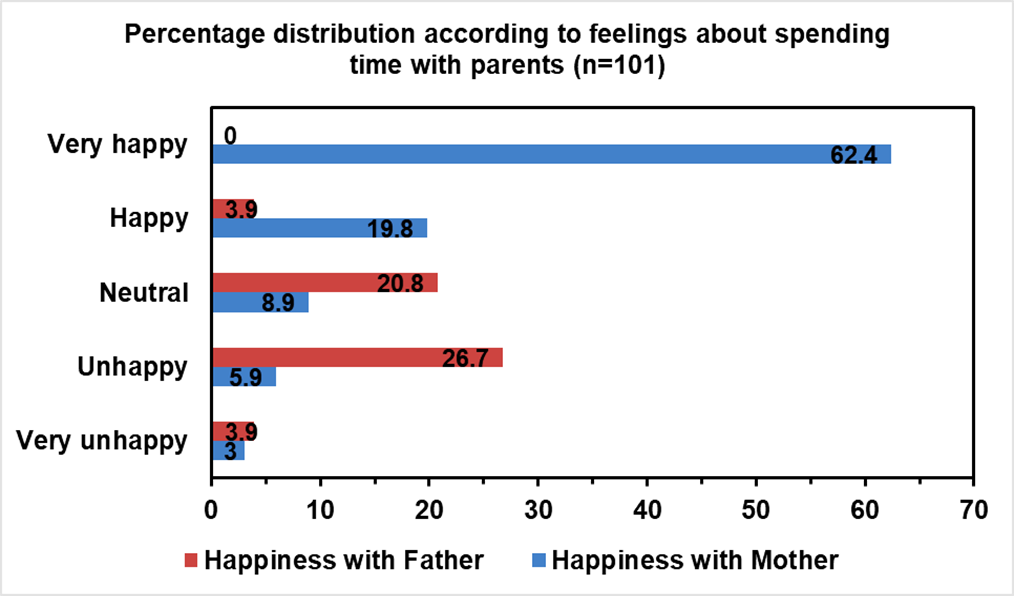

Figure 1. Frequency distribution of feelings about spending time with parents of the respondents.

The frequency of sensations experienced when spending time with participants' mothers is shown in Figure 1. While 5.9% and 3% of participants are sad and extremely unhappy with their mother, respectively. In addition, 62.4% of participants are very happy with their mother, 19.8% are happy with their mother, and 8.9% have neutral happiness performance with their mother (Figure 1). On the other side, the frequency of sensations experienced when spending time with participants' fathers is shown by this graph. While 4% of participants are extremely unhappy with their father. 27% of participants are happy with their father, 49% are very happy with their father, and 21% have neutral happiness performance with their father (Figure 1).

The relationship between relationship-related factors and overall relationship intimacy with the mother is shown in Table 3. Relationship intimacy with the mother has a highly significant correlation with mother-child conflict (P-value 0.001), mother-child closeness (P-value 0.001), mother-child dependence (P-value 0.001), father-child conflict (P-value 0.001), father-child closeness (P-value 0.001), father-child dependence (P-value 0.001), and overall relationship intimacy with the father (P-value 0.001).

Table 3. Distribution of the association between relationship factors and overall relation intimacy with mother (n=101).

| Variables | Overall relation intimacy with mother | Total | P Value | ||

| Low | Medium | High | |||

| Level of Conflict with mother | |||||

| Low | 15 | 7 | 0 | 22 | 0.001 |

| Medium | 13 | 32 | 21 | 66 | |

| High | 1 | 5 | 7 | 13 | |

| Level of Closeness with mother | |||||

| Low | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.001 |

| Medium | 24 | 29 | 3 | 56 | |

| High | 4 | 15 | 25 | 44 | |

| Level of Dependence with mother | |||||

| Low | 8 | 2 | 0 | 10 | 0.001 |

| Medium | 20 | 26 | 4 | 50 | |

| High | 1 | 16 | 24 | 41 | |

| Level of Conflict with father | |||||

| Low | 16 | 7 | 1 | 24 | 0.001 |

| Medium | 12 | 32 | 20 | 64 | |

| High | 1 | 5 | 7 | 13 | |

| Level of Closeness with father | |||||

| Medium | 27 | 34 | 12 | 73 | 0.001 |

| High | 2 | 10 | 16 | 28 | |

| Level of Dependence with father | |||||

| Low | 2 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 0.001 |

| Medium | 23 | 31 | 8 | 62 | |

| High | 4 | 10 | 18 | 32 | |

| Overall relation intimacy with father | |||||

| Low intimacy | 22 | 13 | 3 | 38 | 0.001 |

| Medium intimacy | 5 | 19 | 14 | 38 | |

| High intimacy | 2 | 12 | 11 | 25 | |

The relationship between relationship-related characteristics and overall relationship intimacy with the father is shown in Table 4. In this table, there is a highly significant correlation between the overall relationship intimacy with the father and the degree of mother-parental conflict (P-value 0.000), the degree of father-parental conflict (P-value 0.001), the degree of father-parental closeness (P-value 0.001), and the overall relationship intimacy with the mother (P-value 0.001). Overall relationship intimacy with the father and degree of dependence on the mother have a highly significant association (P-value 0.008). Level of reliance on father and overall relationship intimacy with father had a weakly significant relationship (P-value = 0.079). There is no correlation (P-value 0.113) between overall relationship intimacy with father and degree of closeness to mother.

Table 4. Distribution of the association between relationship factors and overall relationship intimacy with father (n=101).

| Variables | Overall relation intimacy with father | Total | P Value | ||

| Low | Medium | High | |||

| Level of Conflict with mother | |||||

| Low | 18 | 2 | 2 | 22 | 0.001 |

| Medium | 20 | 28 | 18 | 66 | |

| High | 0 | 8 | 5 | 13 | |

| Level of Closeness with mother | |||||

| Low | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.113 |

| Medium | 27 | 18 | 11 | 56 | |

| High | 11 | 19 | 14 | 44 | |

| Level of Dependence with mother | |||||

| Low | 6 | 3 | 1 | 10 | 0.008 |

| Medium | 24 | 12 | 14 | 50 | |

| High | 8 | 23 | 10 | 41 | |

| Level of Conflict with father | |||||

| Low | 18 | 5 | 1 | 24 | 0.001 |

| Medium | 20 | 32 | 12 | 64 | |

| High | 0 | 1 | 12 | 13 | |

| Level of Closeness with father | |||||

| Medium | 38 | 31 | 4 | 73 | 0.001 |

| High | 0 | 7 | 21 | 28 | |

| Level of Dependence with father | |||||

| Low | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 0.079 |

| Medium | 29 | 22 | 11 | 62 | |

| High | 6 | 14 | 12 | 32 | |

| Overall relation intimacy with mother | |||||

| Low intimacy | 22 | 5 | 2 | 29 | 0.001 |

| Medium intimacy | 13 | 19 | 12 | 44 | |

| High intimacy | 3 | 14 | 11 | 28 | |

Table 5 shows the relationship between the participant's gender and their likes and dislikes of their parents. "Things I like most about my mother" (P-value 0.047), "Things I dislike most about my mother" (P-value 0.040), "Feelings when I spend time with my mother" (P-value 0.066), and "Things I dislike most about my father" (P-value 0.058) all have a marginally significant relationship to the gender of the participants. The participant's gender did not significantly affect their ratings of their father's qualities (P-value: 0.808) or their feelings about spending time with their father (P-value: 0.157).

Table 5. Distribution of the association between Gender and Likings about parents (n=101).

| Variables | Gender | Total | P Value | |

| Male | Female | |||

| Things that I like most about mother | ||||

| Cheerful | 6 | 4 | 10 | 0.047 |

| Good Advisor | 9 | 5 | 14 | |

| Great Teacher | 6 | 8 | 14 | |

| Wonderful Cook | 6 | 5 | 11 | |

| Positive minded | 2 | 11 | 13 | |

| Smart Person | 1 | 8 | 9 | |

| Kind Hearted | 11 | 12 | 23 | |

| Stylish Person | 5 | 2 | 7 | |

| Things that I dislike most about mother | ||||

| Not Creative | 36 | 47 | 83 | 0.040 |

| Spend time in social media (Facebook, YouTube) | 10 | 3 | 13 | |

| None | 0 | 5 | 5 | |

| Feelings when spend time with mother | ||||

| Very Unhappy | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0.066 |

| Unhappy | 5 | 1 | 6 | |

| Neutral | 5 | 4 | 9 | |

| Happy | 9 | 11 | 20 | |

| Very Happy | 24 | 39 | 63 | |

| Things that I like most about father | ||||

| Cheerful | 11 | 7 | 18 | 0.808 |

| Good Advisor | 12 | 16 | 28 | |

| Great Teacher | 3 | 2 | 5 | |

| Wonderful Cook | 3 | 3 | 6 | |

| Positive minded | 2 | 2 | 4 | |

| Smart Person | 3 | 7 | 10 | |

| Kind Hearted | 11 | 16 | 27 | |

| Stylish Person | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Things that I dislike most about father | ||||

| Not Creative | 38 | 47 | 85 | 0.058 |

| Spend time in social media (fb, yt) | 8 | 3 | 11 | |

| None | 4 | 1 | 5 | |

| Feelings when spend time with father | ||||

| Unhappy | 3 | 1 | 4 | 0.157 |

| Neutral | 11 | 10 | 21 | |

| Happy | 15 | 12 | 27 | |

| Very Happy | 17 | 32 | 49 | |

This study aimed to investigate the quality of parent-child relationships among teenage higher secondary pupils. The findings revealed that over 60% of the participants reported high satisfaction with spending time with their mothers, whereas almost half of them expressed similar satisfaction with their fathers. Conversely, only 3.5% of participants reported dissatisfaction with their relationships overall. Notably, no participants reported being very unhappy with their fathers, while 3% reported being very unhappy with their mothers. These results align with prior research which demonstrated that high parent-child connectedness fosters mutual respect, emotional support, enjoyment of shared time, and open communication, while reducing hostility and resentment [8]. Furthermore, the study found that perceived overprotectiveness by fathers was associated with increased hostility from children toward them [15].

The percentage of respondents who report having disagreements with their mothers is about equal to the percentage who report being dependent on them. While a sizeable portion (about half) report being extremely dependent on and connected to their mothers. Contrarily, the results show that about three-quarters of respondents had disagreements with their fathers, despite a similar number of respondents being close to and dependent on them. While a sizeable portion report being extremely dependent on and close to their father. These results align with prior research on the complex balance of conflict and attachment in parent-child relationships. [16]. A small group (15.8%) reported that their father told them they are worthless while 25.7% of the participants answered they never felt that way. Research suggests that college students often revert to familiar problem-solving strategies when navigating novel or emotionally charged situations [17]. In the current study, overall relationship intimacy was slightly higher with mothers compared to fathers, indicating subtle differences in relational dynamics [18]. The results revealed that over 40% of respondents reported low overall closeness with their father, while just under 30% indicated low closeness with their mother. In contrast, the remaining respondents described medium or high levels of intimacy with their parents. Furthermore, closeness and overall relationship intimacy were associated with levels of parental conflict and relationship closeness. This may stem from perceptions that overprotective parents restrict their children's independence [19]. As a result, children may harbor resentment toward their parents due to limited autonomy, potentially leading to diminished communication [20]. In their investigation of the relationship between parenting styles and academic achievement, Hayek et al. found that authoritative parenting exerts a greater impact on children's high achievement than parental involvement, whereas parental involvement in children's academic development has a positive indirect effect [21].

This study investigated that there is a highly significant correlation between the overall relationship intimacy with father and the degree of mother-parental conflict (P-value 0.000), the degree of father-parental conflict (P-value 0.001), the degree of father-parental closeness (P-value 0.001), and the overall relation intimacy with mother (P-value 0.001). Fathers play an important role in the health outcomes of adolescents [22]. In addition, this study also has examined the association between participants' gender and their preferences and aversions toward their parents. A marginally significant relationship was observed between participants' gender and the characteristics they most liked (P = 0.047) and disliked (P = 0.040) about their mothers. Additionally, marginally significant associations were found for feelings experienced when spending time with the mother (P = 0.066) and behaviors the father does best that the child finds annoying (P = 0.058). These findings align with prior research indicating that women perceive mothers as more nurturing than fathers [5, 23]. Furthermore, the results align with earlier observations that no significant gender differences emerge when averaging scores on the "protection" scale. It also supports previous evidence demonstrating that parent-child relationships among young adults are generally comparable across male and female dyads [24]. Moreover, healthy parent-child bonds may reduce risks of poor adjustment and promote resilience in adolescents [15, 25]. Similar public health concerns have been raised about mental health, food and lifestyle behaviors, nutrition status, which significantly affect students in Bangladesh [26, 27]. This study has certain limitations, including a relatively small sample size, which restricts the generalizability of the findings to adolescents or young adults across Bangladesh. Therefore, larger-scale studies are recommended to provide a more accurate understanding of this issue.

This study highlights the importance of parent-child bonds in shaping adolescents’ emotional and relational development. The findings indicate broadly comparable patterns across the key relationship aspects including conflict, closeness, and dependence with slightly stronger bonds reported with mothers than fathers. Gender showed marginal associations with specific perceptions of mothers, however no significant effect was found regarding relationships with fathers. This study found no clear link between how much participants liked or disliked their fathers and the time they spent with their parents. However, almost all aspects of the parent-child relationship were strongly connected to overall intimacy, showing that these factors are closely related. The findings give useful insights into how adolescents in Bangladesh relate to their parents, but the small sample size limits how widely the results can be applied. Future studies with larger and more diverse groups, as well as different ways of measuring parent-child bonding, are needed. It is also important to explore how family income and size affect these relationships. In addition, community awareness programs could help promote stronger and healthier parent-child connections, which may support better adolescent well-being.

We want to acknowledge and gratitude for the administrative and resource supports provided by the Chattogram Biggan College and Chattogram Commerce College, in the Chattogram city of Bangladesh.

The study was conducted to fulfill an academic purpose. There were no funding sources available for this study.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Review Committee (ERC) of the Faculty of Health and Life Sciences (Ref. FAHS-ERC-25-2022), Daffodil International University, Bangladesh. A written informed consent was obtained before the interview. Since the study participants belong to the age group below 18 years, the data collectors obtained consent from their parents over the phone while interviewing them. The confidentiality of the information collected from the respondents was well maintained.